WILD IDEA – The Whidbey Institute Story by Fritz Hull

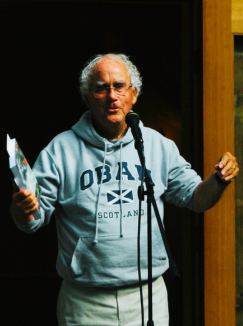

I recently had the honor to sit down with Fritz Hull to talk about his latest book, “Wild Idea.” Published this past year, “Wild Idea” tells of how a seemingly crazy idea became a sizable force for good – the Whidbey Institute. We met at his family’s Hilltop Cabin in Legacy Forest. Built 10 years ago on 5-acres of land that is part of the original 1966 farm purchase, the cabin provided us with a peaceful setting to explore some of the ideas he shares in the book, the inspiration of the early Chinook days, and what the future might hold for the land and those who visit it.

I recently had the honor to sit down with Fritz Hull to talk about his latest book, “Wild Idea.” Published this past year, “Wild Idea” tells of how a seemingly crazy idea became a sizable force for good – the Whidbey Institute. We met at his family’s Hilltop Cabin in Legacy Forest. Built 10 years ago on 5-acres of land that is part of the original 1966 farm purchase, the cabin provided us with a peaceful setting to explore some of the ideas he shares in the book, the inspiration of the early Chinook days, and what the future might hold for the land and those who visit it.

What were the origins for this book?

About four years ago I felt the need to write the story of Chinook/Whidbey Institute, and so I began a long and fairly demanding task. I wrote it for those who have had significant experiences here, who want to remember the earlier times, and want to see their time here in the larger sweep of the organization’s journey. I have been asked a lot about the early community, those who were with Vivienne and me, who formed the early work, led workshops, proceeded always by consensus, and set the whole enterprise in motion. Who were they? What held them together? How were they inspired? I love these questions because I feel a growing respect for those who built this place and steward it so faithfully. But I wrote it even more for those here now, and for those who are coming. This long 50-year story had never been written and I felt it was essential that I could hand people the story, for now it is also their story as they build the future. Read More →

I recently had a chance to sit down with Larry Rohan, the Whidbey Institute’s new Forest Steward. Larry embodies a deep-rooted passion for the natural world, cultivated over a lifetime of exploration and study. With a BS in Forestry from Purdue University and experience with the US Forest Service and Alaska native tribes, Larry brings a wealth of knowledge to this new role at the Whidbey Institute. His work is driven by a profound understanding of the interconnectedness between forests, soil, and climate and his dedication to conservation and environmental stewardship is not only a testament to his commitment to creating a better world for future generations.

I recently had a chance to sit down with Larry Rohan, the Whidbey Institute’s new Forest Steward. Larry embodies a deep-rooted passion for the natural world, cultivated over a lifetime of exploration and study. With a BS in Forestry from Purdue University and experience with the US Forest Service and Alaska native tribes, Larry brings a wealth of knowledge to this new role at the Whidbey Institute. His work is driven by a profound understanding of the interconnectedness between forests, soil, and climate and his dedication to conservation and environmental stewardship is not only a testament to his commitment to creating a better world for future generations.