On our 100 acre woodland campus, we cultivate place together—collaborating with nature and one another to learn better how to relate to our planet, our built environment, and our human and other-than-human communities. Our gardens, forest trails, and buildings provide a context in which and from which to learn and grow.

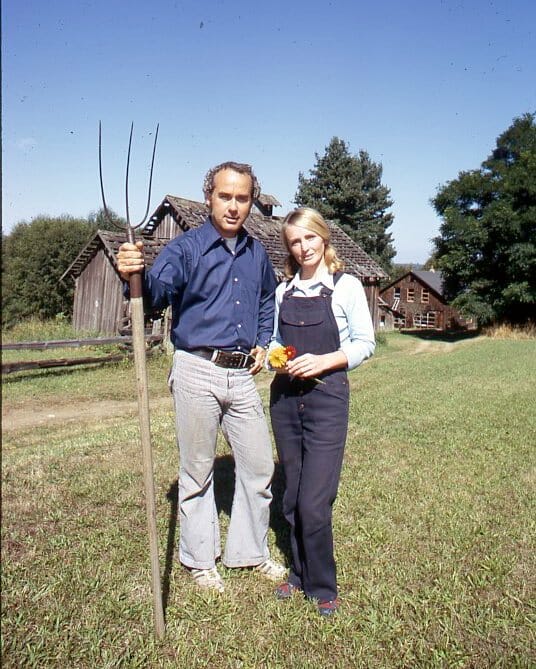

When Land Steward Robert Mellinger joined our team, he had the opportunity to work alongside outgoing Steward Maggie Mahle. Bringing his own background in liberal arts, journalism, wilderness ecology and education, permaculture design, and wildlife tracking, he has helped enrich our culture of land stewardship.

“Maggie so strongly embodied an ethic that is so hard for most of us to live up to, which is to spend more time listening than talking. Her patience was extraordinary,” he said. “To get to know the Institute through her eyes, and through her stories, will influence the way I interact with the world for the rest of my life.”

“The real, hard ecological work ahead of us requires first falling in love. That’s difficult to do without spending the time getting to know what’s around us, deeply.”

—Robert Mellinger

Robert feels a sense of excitement about working alongside other community members on this land, and welcomes the stories of all who have been involved with Chinook. “It’s been important to get a sense of the deep history of the Institute, and of all the different people who have contributed to creating this place and holding this place in a way that makes what we’re doing today possible.” He hopes to hear more of those stories, and envisions a future in which we can welcome even more community members into a relationship with this land. “Because the Institute focuses on looking at ecological issues in all their dimensions, from community to leadership to ecosystem vitality, it’s a good place for community to being understanding ecological design, in the sense of participation—‘I’m a person, a community member, and we interact with our landscape and change it.’” Robert hopes that the Institute can foster both a love of nature and a sense, in the individual, of what one’s participation means in the dynamics of natural systems.

“The land is always there, quietly offering its wisdom. Though our task as stewards may be to care for the land, the land has its own needs, and messages for us which only a deep listening can discern so that we can better focus our energy. The earth becomes an ally, and I’m reminded always how much our love and attention and care matters.”

—Maggie Mahle, former Land Steward

“Without a return to a responsible co-existence with the Earth we are truly lost, both physically and spiritually.”

—Kirk Webb, Landscape of the Soul program FACILITATOR

deer photos, top 3: © Marnie Jackson, Bottom 1: © Gordon LEe

“The garden is like the center of a web of relationship, not only with all the people who have worked there over the years abut also with the places that the plants come from.”

“The garden is like the center of a web of relationship, not only with all the people who have worked there over the years abut also with the places that the plants come from.”

“As a newcomer to South Whidbey, just working with neighbors in the garden made me feel a different sense of belonging. The things that come up when you’re just chatting and picking beans are really cool. I’ve had long chats about water conservation with a volunteer at Good Cheer, and about music, kids, and different things. That’s one of my favorite parts of working with volunteers.”

“As a newcomer to South Whidbey, just working with neighbors in the garden made me feel a different sense of belonging. The things that come up when you’re just chatting and picking beans are really cool. I’ve had long chats about water conservation with a volunteer at Good Cheer, and about music, kids, and different things. That’s one of my favorite parts of working with volunteers.”