“The Sanctuary holds space for deep contemplation, for reflection, and for small gatherings that invite connection between people. As important is the seamless and visible connection with natural world,the spirit within, and the people who grace the building.” From a 2014 Whidbey Institute Newsletter article remembering Judith Yeakel.

The Sanctuary at Chinook is a study in balance—it is equal parts humble and grand, grounded and soaring, cozy and spacious. It is of the earth, and of the spirit. It is, for many, a place of refuge and a source of inspiration.

This building has many to thank for its creation—philanthropist Judith, who funded its construction; craft builder Kim, who dreamed into the possibility of rendering a humble chapel in stunning live edge wood; architect Ross, who helped move the project from conception to harmonious execution in an evolving, collaborative process; Chinook founders Fritz and Vivienne, who saw the need for a space to celebrate both the inner life and the outer wonders; Michael, project manager and former Whidbey Institute board member, who bridged the hopes and needs of the organization with the vision and processes of the construction team; and many community members, who labored joyfully over the building’s design and assembly.

Crafted by many, it has become a sanctuary for many faiths. Chinook founder Vivienne Hull remembers the beautiful dedication which was held after the construction of the sanctuary. It included a parade of banners from the Procession of the Species, a Native American blessing, and a rich and diverse interfaith program. “It was quite phenomenal,” she said. “Prayers were shared from most of the world’s religions.”

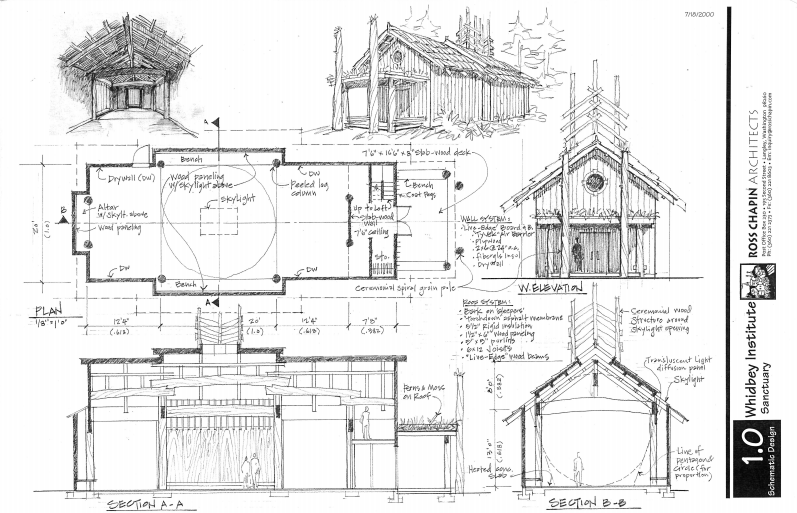

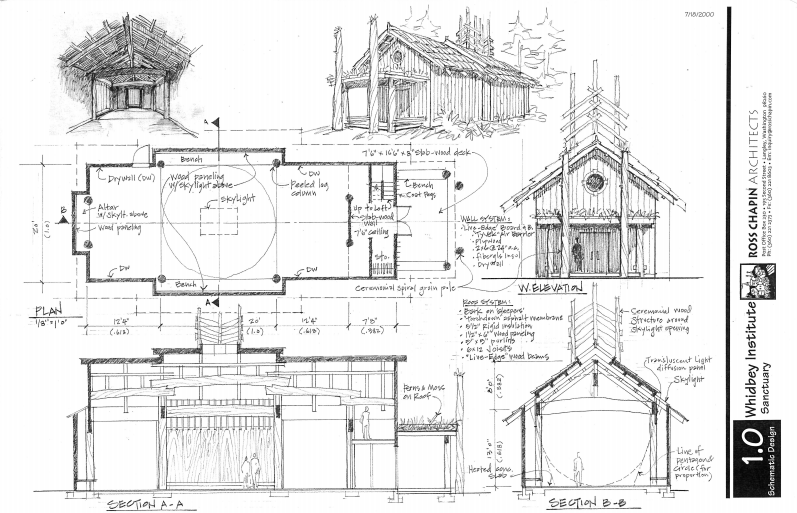

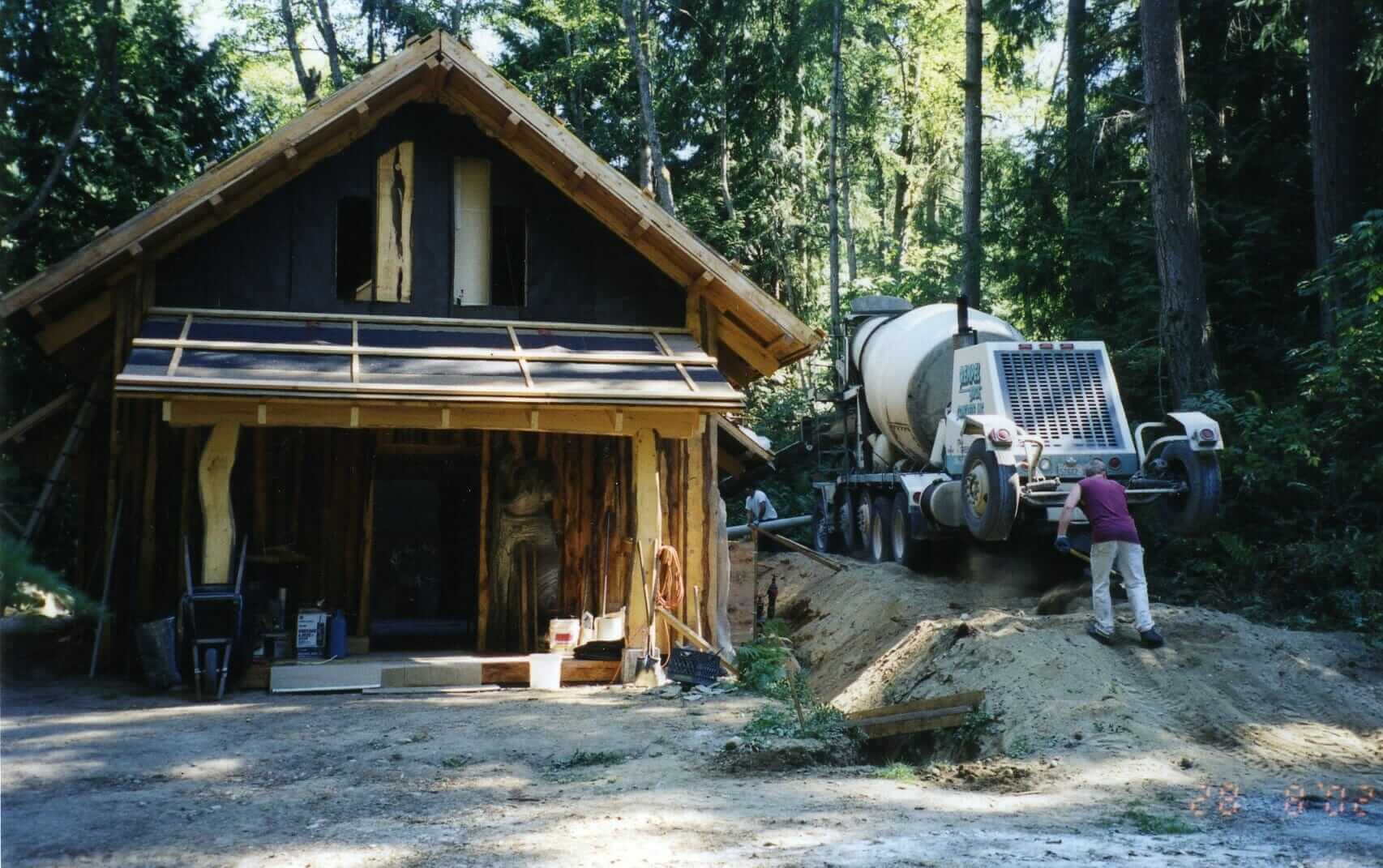

The dedication of the Sanctuary was the culmination of years’ toil and dreaming. The work began in earnest when, in the summer of 1999, a call went out for concepts for a sacred space to be built on Whidbey Institute grounds with a generous gift from Judith Yeakel. Ross Chapin submitted not one sketch but many—a series of drawings which described key concepts and principles which might inform the project. Grounded in the earth. Looking toward the sky. Surrounded by trees, as a “council of elders”, and inviting an experience of procession and arrival.

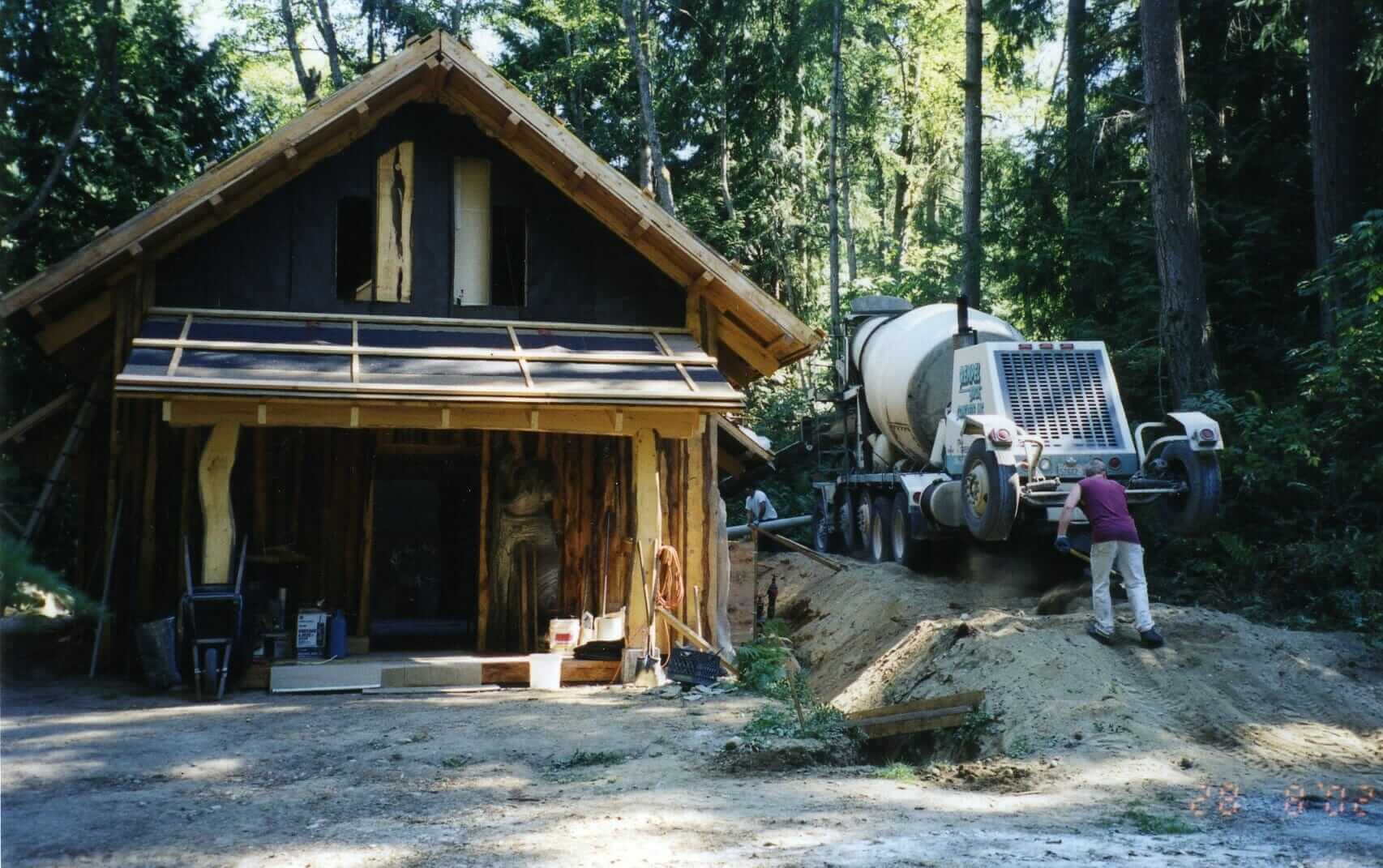

Meanwhile, Kim Hoelting was conceiving of an organic, unique wooden chapel—traditional in form, rich in texture, inspired by its surroundings and handcrafted from beautiful wood. By 2000, creative sparks were flying as the two friends collaborated on a design which marries the magic of a forest hideaway with the geometry of a classic church, measured throughout by the golden ratio.

Meanwhile, Kim Hoelting was conceiving of an organic, unique wooden chapel—traditional in form, rich in texture, inspired by its surroundings and handcrafted from beautiful wood. By 2000, creative sparks were flying as the two friends collaborated on a design which marries the magic of a forest hideaway with the geometry of a classic church, measured throughout by the golden ratio.

This building is inspiring beyond its size. One visitor was quoted as saying, “I’ve been all over the world, in sacred spaces in Burma, India, and Africa, and none has touched me the way that the Sanctuary does.” It holds many secrets, hidden in plain sight—its porch, for instance, is one giant slab of salvaged Sitka spruce.

At Woodland Hall, off Maxwelton Road, builder Kim Hoelting stores part of his one-of-a-kind collection of old-growth and salvaged wood. “The Board [of the Whidbey Institute] came down here, and we sat on a big slab of wood,” Kim said, “They asked if I could imagine what this building might be, and I said that in my mind’s eye it would be something that’s like a Native American Longhouse, but which feels as though you’re a kid, crawling into a stump and looking out through the cracks. I patted the block of wood we were sitting on and said it was going to be the front porch.”

Kim seems to know every piece of wood in the building, describing them like friends. The porch was once a 9-ft. diameter old growth spruce tree which fell in a 1991 windstorm at Olympic National Park’s Lake Quinault Lodge. “It smashed a bunch of cars,” Kim told me, “and was milled in Elma.” The wood in the gable above the front porch was salvaged from the same windstorm, he said, while the shakes on the porch and roof were salvaged from the Humptulips River drainage basin and hand-split on Whidbey by builders and volunteers. Other large slabs for the project were hand-selected in Southeast Alaska.

“The building is rough and rugged on the outside and refined on the inside,” said Michael Hansen, who served as project manager and as liaison between the board and building teams. “The construction was a very fluid process, though we needed a talking stick at one point to resolve the question of whether the main sanctuary should or should not have windows. It was a tough discussion, settled in two philosophical camps—do you look to nature, or do you look inward?”

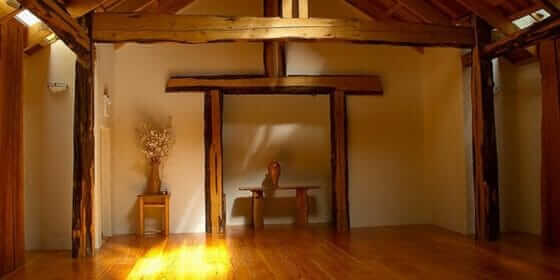

The results of this teamwork are stunning: skylights let in the sun; light from hidden windows draws the eye to the altar at the far end of the space; and richly textured interior spaces leaves a visitor with the sense of being held within a living forest.

One does not march directly into the Sanctuary. A visitor steps first into a shadowed foyer, face-to-face with a unique slab of wood seemingly grown out of a stone on the floor.

“The tree on the stone, that’s art. That’s Kim,” Ross said. “It stops you in your tracks, but it opens you to another universe if you really stop and behold the mystery that is that tree.

“The walk in the woods—the getting there—is important. You see something, you’re drawn in, and as you go on there’s an experience of procession. You come upon a meadow. What’s that? It’s tucked away. You approach, you open the door, and you smell this amazing aroma of wood. The ceiling is low, and the light is dim, and your coats come off. And then you see this wood . . . it could be the end of your journey, this tree on this stone. There’s light coming through. You’re drawn in not straight on, but askance—from the side. The ceiling goes up, and up, and up . . . That’s where form and human experience come together.”

The building holds many stories. Kim remembers the camaraderie of the building team, which he called “an odd collection of people with a playful sense for wood.”

“This was one of my favorite collaborations with Ross,” he said. “Beno Kennedy, Gordon Sandstad, Sky Hoelting, and Jim Shelver were on the team. Lon Peterman did the siding. Michael was incredible—a stabilizing force, taking a lot of feedback from many people and bringing it into working form.

“We put in afternoons up there and spent our mornings on other work, which made a project which might have taken six or seven months stretch over a year. It allowed us the freedom to push the pause button if the weather flared up, or if we were stuck. That’s part of the reason the building turned out as cool as it did.”

Ross remembers one moment when the Sanctuary was touched by events in the world at large. “Detail is utterly important to me,” he said. “The curve of the wood, the shaft of light, the height of a beam. One day I walked up to the site and gasped.”

Ross’s surprise was caused by a beam, already in place, which he recognized as having been prepared upside down. When he learned the circumstances of its production, he realized that the flipped piece was part of an important story.

“I found out that as this beam was being finished and adzed, Gordy got news that a plane had crashed into one of the Twin Towers. Instead of stopping his work, he refocused. He stayed on that beam all that day and all the next day. Meanwhile, human culture was turned upside down.”

Like people, buildings are shaped by the events of their upbringing. This building has been shaped by brilliant collaborations, insightful vision, clear intentions, and a careful resolution of tensions into harmony.

“I remember the community of workers and what happened between and among us while we were there,” Kim said. “We did work that was true and authentic—a real expression of who we are in the world and what we hope to become. My greatest hope is that all of us can find that little, holy place in all that we do—that we can dare to make it a real expression of who we are in the moment, and what we see, and what we feel. It doesn’t matter if you’re a janitor, or a neurosurgeon, or a carpenter—with courage and fortitude, what you love should be able to bubble up out of you. That’s what the Sanctuary means to me.”

Plan and Elevation by Ross Chapin Architects

January 11, 2016

Those of you who have visited the Whidbey Institute recently may have noticed a mound of logs being laid around the parking lot at Thomas Berry Hall. What you are seeing is the construction of a hedgerow and restoration of the north-facing slope.

Those of you who have visited the Whidbey Institute recently may have noticed a mound of logs being laid around the parking lot at Thomas Berry Hall. What you are seeing is the construction of a hedgerow and restoration of the north-facing slope. These hedgerows are made in many different ways, but all are given structure by woody plants like hawthorn, oak, and hazel. Sometimes the plants are “laid,” planted in a row and then bent over onto each other so that they form a sort of woven fence. Others are tall rock walls with massive oak roots binding it all together. Still others are gentle, low mounds of earth and rock that are covered in wildflowers and studded with coppiced hawthorn.

These hedgerows are made in many different ways, but all are given structure by woody plants like hawthorn, oak, and hazel. Sometimes the plants are “laid,” planted in a row and then bent over onto each other so that they form a sort of woven fence. Others are tall rock walls with massive oak roots binding it all together. Still others are gentle, low mounds of earth and rock that are covered in wildflowers and studded with coppiced hawthorn. The questions were, did it make sense, and how would we make it?

The questions were, did it make sense, and how would we make it? The method has many applications from garden beds to hedgerows. The basic idea is that the wood decomposes over time, creating a spongy, nutrient rich mass that is great for plants. In places with dry summers, this spongy mass holds a tremendous amount of moisture and can reduce or eliminate the need for watering, depending on what and where you are growing.

The method has many applications from garden beds to hedgerows. The basic idea is that the wood decomposes over time, creating a spongy, nutrient rich mass that is great for plants. In places with dry summers, this spongy mass holds a tremendous amount of moisture and can reduce or eliminate the need for watering, depending on what and where you are growing.

Meanwhile, Kim Hoelting was conceiving of an organic, unique wooden chapel—traditional in form, rich in texture, inspired by its surroundings and handcrafted from beautiful wood. By 2000, creative sparks were flying as the two friends collaborated on a design which marries the magic of a forest hideaway with the geometry of a classic church, measured throughout by the golden ratio.

Meanwhile, Kim Hoelting was conceiving of an organic, unique wooden chapel—traditional in form, rich in texture, inspired by its surroundings and handcrafted from beautiful wood. By 2000, creative sparks were flying as the two friends collaborated on a design which marries the magic of a forest hideaway with the geometry of a classic church, measured throughout by the golden ratio.